Refiguring Kampani Art

Company School (Kampani kalam) is a broad term used by art historians to describe a variety of hybrid Indo-European style of paintings that developed in India in the 18th and 19th centuries by Indian artists under the patronage of various East India Companies. In one of its early definitions, the style was thought to blend traditional elements from Rajput and Mughal painting with a more Western treatment of perspective, volume, and recession, and usually reflected a change in medium from gouache to watercolor or sepia wash on European paper.[1] Most Company paintings were described as small and intimate, reflecting the Indian miniature tradition, although natural history paintings of plants and flora were usually life-size.

If Company style botanical art tradition (or traditions) can be defined at all, it refers to a unique visual tension between the naturalistic depiction of individual 'specimens' drawn from Western botanical illustration against the lingering intimacy, stylization and flat depiction of composite floral or plant 'types' drawn from Indian miniature and narrative painting styles. Although this tension refers to heuristic divisions that are not always so clearly drawn in life, the former view could be said to rely more on empirical observation of nature - the real thing in its natural habitat - while the latter does not shy away from the idea of the flower as motif, as pattern. Indeed, art historians characterized high Company style - coinciding with the golden age of botanical illustration - as some combination of the following: rich opaque watercolor heightened by gum arabic, a highly developed sense of pattern (if not perspective), little or no empty space around the images, and a diagonal layout such that the plant appears to spill over - literally grow over - the paper edge.[2]

Lately, however, Kampani kalam has come in for criticism, not least because of the "pejorative whiff of colonialism" implied by the name itself, and all that such a label excludes. Surely, argues Henry Noltie, a school of painting should not be named for its corporate East India Company sponsor but for its primarily Indian artists, the real foot soldiers in this genre.[3] Still others point out that the Company School’s alleged difference from late Mughal art, a hallmark of earlier definitions, is a false distinction – given that the same artists were often working in different styles for different patrons.[4] Also missing from Company School, given its past North Indian bias, is the great variety of South Indian vernacular traditional artists, such as the Tanjore moochy castes or jingars from Trichy, whose role in botanical art remains for the most part unexplored.[3] And finally, there is the time period and therefore the art medium assumed by Company School as a category. If the label refers only to the British East India Company-sponsored watercolors from mid-18th century that peaked by the mid-19th century, then what are we to make of botanical art sponsored by other East India Companies (Dutch, Danish, French) that preceded the British, and produced botanical art in media other than watercolor? Such as the extraordinary drawings and copperplate engravings of the 17th century Dutch Hortus Malabaricus. Or the amateur European women artists, neither native Indians nor professional botanists, who created much of the art for the colonial flora of the Nilgiri hills.

Below are some of these forgotten or unnamed artists and indigenous collaborators left out by Kampani kalam whose names are slowly being reinserted into the Indian botanical art archive by a handful of diligent scholars.

MALABAR

Antonin Goetkint (artist)

Marcelis Spljinter (artist)

Bastiaan Stoopendael (engraver)

Gonsalez Appelman (engraver)

Father Mathew (artist, compiler)

Itty Achuden (physician-collector)

Appu Bhatt, Ranga Bhatt &

Vinayak Pandit (physician-collectors)

COROMANDEL/CALCUTTA

Tanjore moochy/jingars

Vishnu Persaud (Vishnu Prasad)

Bhawani Das and Gorachand

Rungiah & Govindoo (Coromandel)

Lakshman Singh (Calcutta)

Cheluviah Raju (Lalbagh)

Raja Serfoji list of 3 Rajus

NILGIRIS

Lady Bourne’s artists (30)

Shembaganur artists (5)

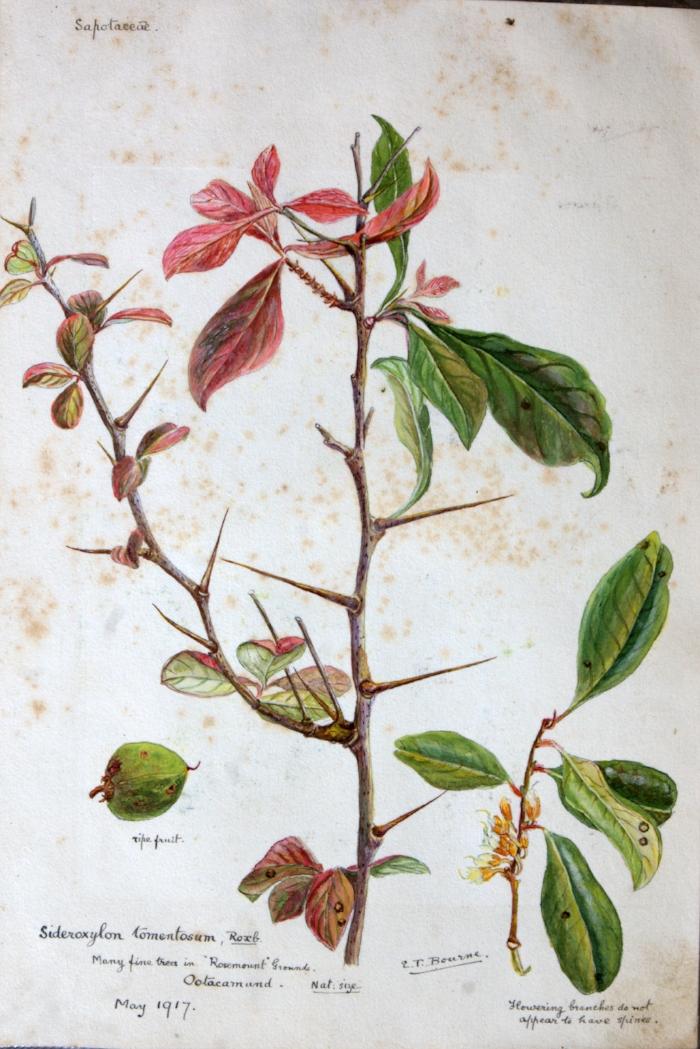

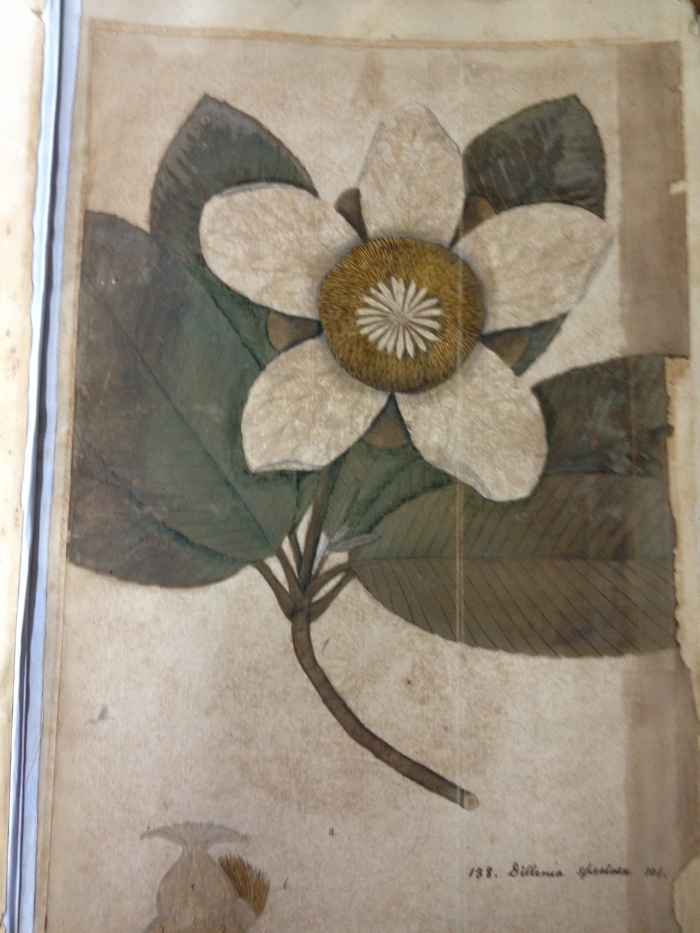

In the pages ahead, we will encounter some of these names in three plant geographical regions - Malabar, Coromandel, and Nilgiris - through the art produced for three pioneering botanical texts or image collections: the 17th century Hortus Malabaricus (black and white copperplate engravings), the mid-19th century Roxburgh Icones and Plants of the Coast of Coromandel (hand-colored engravings, watercolors and lithographs), and the early 20th century Ootacamund Flowers (watercolors) that later made their way, as prints, into the Flora of the South Indian Palni Hills.

IMAGE DETAILS

Row 1: Original drawings, Hortus Malabarici Icones and Copperplate engravings, Hortus Malabaricus, 1678-1691

Row 2: Lithographs after b/w drawings and watercolor paintings, Plants of the Coast of Coromandel, 1795-1820

Row 3 :Watercolor paintings, Ootacamund Flowers, 1910-1919